Welcome to another entry in the Oscar Film Journal!

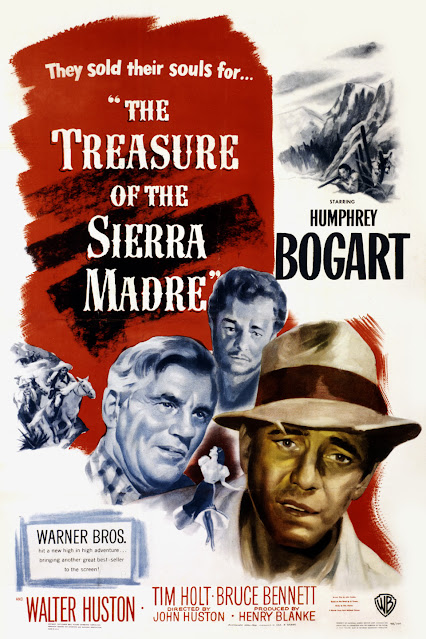

Today I'll be talking about a highly influential film from the 1940s, considered a career highlight for its writer/director and its two main stars, and essentially a film noir/Western mashup, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. One of John Huston's most acclaimed works, based on the 1927 novel by mysterious author B. Traven, this is the story of three gold prospectors who venture into the unforgiving Sierras to dig for gold and find their fortune.

The main character in the book is grizzled prospector Howard (played to perfection in this film by John's father Walter Huston in one of his last film roles), the only one in the group with gold mining experience and the most likable of the story's three scoundrels. In the film version the focus is shifted a bit more to Fred Dobbs, played by Humphrey Bogart in a dirtbag performance delivered with scummy relish (Bogart was infamously snubbed by the Academy for this role). Dobbs begins the film as a down-on-his-luck American drifter in Mexico, looking for work and begging for cash, and that's about as nice as this character ever gets. As he and his partners amass a fortune in gold, Dobbs descends into paranoia and violence, providing the film's strongest character arc. The third partner Bob Curtin is played by veteran Western actor Tim Holt, in a performance that sort of takes the opposite trajectory to Bogart's. Curtin starts out as a fellow drifter and gradually becomes more honorable as the story progresses; if we root for anyone in this film it's Curtin.

At a time when Hollywood Westerns were sanitized, good vs. evil morality plays, Sierra Madre made use of film noir tropes such as intense lights and shadows, Expressionist camera angles, and above all the deeply flawed protagonist to create a grimy, almost psychological location drama far ahead of its time. The three main characters start out penniless and homeless, and by the end of the film they all appear in significantly rougher shape, sporting unkempt beards, caked-on dirt, and sinewy sweat. This is one of the more palpably grungy-looking films of the period and must've been an influence on 1960s spaghetti Westerns (Steven Spielberg also cited this film as an inspiration when shooting Raiders of the Lost Ark).

Like most film noir stories, Sierra Madre focuses on the characters' response to their situations and surroundings, moreso than on the Macguffin (the gold in this movie assumes much the same role as the titular Maltese Falcon, merely an object for the characters to scheme and argue over). Curtin is content to split the earnings three ways and has no designs on doublecrossing his partners (minus one fleeting moment early in the film). Howard, a longtime prospector with nothing to show for it, warns his compadres of the pitfalls of greed and gold-digging, too old and tired to let any obsessions get in the way now. But Dobbs is distrustful from the start, suggesting that each of them divide up their earnings and hide them each night, lest anyone be tempted to take more than his share. By the end of their excursion he's frantic and unhinged, talking to himself and openly threatening to shoot his companions, fully convinced they're conspiring against him. Bogart's portrayal is uncomfortable to watch (in a good way), as he becomes consumed by avarice and suspicion, much in the same way Daniel Day-Lewis's performance in There Will Be Blood makes your skin crawl.

Bolstered by strong lead performances, particularly the slimy one from Humphrey Bogart and Walter Huston's morally superior pragmatist, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is a very effective study of the three principle characters, but also an immersive look at the austere conditions of gold prospecting and the lengths/depths to which men sink in search of wealth. How little things have changed in a hundred years....

I give the film ***1/2 out of ****.

No comments:

Post a Comment